After the recap ,

American Cinematographer contributor Herb Lightman dives into

the technical aspects of the film, noting that effects are

highlighted right out of the gate after the opening credits

with Seaview's famous "emergency

blow" surfacing

sequence    |

|

|

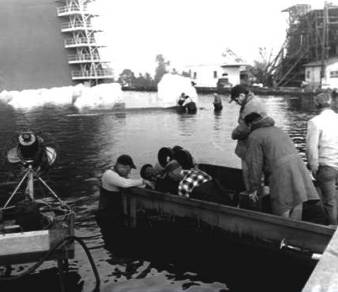

Technicians prepare barge mounted camera

for filming of

Technicians prepare barge mounted camera

for filming of

Seaview (mid-upper center, "ice bergs" behind her.)

|

|

The

initial dramatic scene was shot on Fox's Sersen

Lake, as were all "surface" effects

shots. The

polar sea is seen to boil up as our favorite futuristic sub

leaps out of the water and comes to rest on the surface. To

produce the action, 20th Century Fox's Special Effects Department,

under the supervision of veteran effects expert L.B.

(Bill) Abbott, ASC, constructed an approximately 17',

3" model of Seaview, one of three

different scale miniatures built for the shooting. (*Note

--the article incorrectly refers to the model's length

as 20 feet.) The

model was positioned below water

in a pit created in 1953 for the shooting of Fox's 1954

release, Titanic. By

means of a trip release and a winch with a line attached

to the sub, the craft's natural buoyancy was accelerated

for the "jump-up" effect. The

initial dramatic scene was shot on Fox's Sersen

Lake, as were all "surface" effects

shots. The

polar sea is seen to boil up as our favorite futuristic sub

leaps out of the water and comes to rest on the surface. To

produce the action, 20th Century Fox's Special Effects Department,

under the supervision of veteran effects expert L.B.

(Bill) Abbott, ASC, constructed an approximately 17',

3" model of Seaview, one of three

different scale miniatures built for the shooting. (*Note

--the article incorrectly refers to the model's length

as 20 feet.) The

model was positioned below water

in a pit created in 1953 for the shooting of Fox's 1954

release, Titanic. By

means of a trip release and a winch with a line attached

to the sub, the craft's natural buoyancy was accelerated

for the "jump-up" effect. |

Within the sub

model itself, high-pressure water hoses connected to the

ballast vents produced the effect of water gushing forth

from the sub as it surfaced.

The

addition of detergent added to the water created the desired

effect of foaming turbulence. The spectacular opening

shot duplicates a real "emergency blow" surface

maneuver which producer Irwin Allen was familiar with from

his research efforts. |

|

Foaming water gushes from ballast vents.

Foaming water gushes from ballast vents. |

|

An effective scene early

in the film shows the submerged Seaview gliding through dark

waters beneath a "ceiling" of polar ice. The

bergs begin to disintegrate and huge chunks of ice crash down

on the stricken sub. The icebergs, Abbott explained, were

created out of individual metal frameworks covered with wire

mesh. Over these were placed several thicknesses of cheese cloth,

then the assemblies were |

| covered with wax.

A major problem was getting the various sized iceberg props (size,

4 to 24 inches) to descend at the right speed in order to look

realistic. Each

was individually weighted so as to have relative buoyancy; the

smaller bergs had to fall at the same rate as than the larger

ones. The icebergs were arranged on planks overhead above the

water's surface and dropped into the studio tank by technicians

as the camera rolled. The

divers had to retrieve the various iceberg miniatures and realign

them for the retakes and shots to follow. Note--underwater

shots were filmed in the studio "tank," as opposed

to the Sersen Lake, which for the most part was only several

feet deep and used exclusively for filming surface shots. |

|

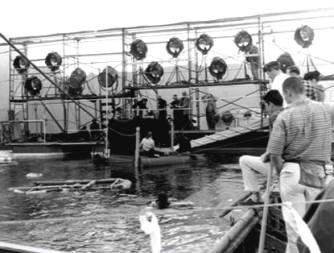

Studio

tank with rows of attendant lights and other gear. |

The movie's four principal models. the 17-plus, 8 and 4 foot

models and the

generic teardrop sub taken out of storage for the

1964 season of the TV show. |

|

In

addition to the 17-plus-foot model used for surface shots,

there was also an eight-foot model for underwater shots in

the Fox tank, and

an approximately four-foot model which was built to scale for

the octopus attack sequence. The octo attack scenes were

shot in a relatively small aquarium type tank as a technical

assistant manipulated the model by hand. |

| For the sequence in which the

mini-sub exits Seaview to head forward to the nose to free a

mine from the sub's searchlight casing, the large model, built

specifically for surface shots, was submerged in the tank in

a stationary position. |

| It was equipped with

an electrically controlled hatch from which a small eleven-inch

model of the mini-sub could be released, guided by fine wires,

which carefully lit, were invisible on screen. |

A larger

model of the mini-sub was built to a scale carefully calculated

with respect to the explosion which was to demolish it, so

that the explosion would appear as real as possible. The

result was viscerally effective, as the larger scale mini-sub

model was actually blown up, the explosive charges planted

within, and the resulting footage processed against a matte

of Seaview's observation nose ports.

Mouse-over at right for dramatic result.    |

|

|

| In a special effect

project such as this, Abbott explained, the studio's miniature

prop shop contributes substantially. Herb

Cheek, head of the shop and considered one of the top experts

in the business, supervised the construction of the various

models required. |

| Virtually

all of the underwater scenes for Voyage were staged in the studio

tank, as pictured at (right)--60 feet square and 11 feet deep. The

special effects photography was done with the camera mounted

in an open-top

"diving bell" camera barge (see below) set into the tank. Pontoons

attached to the sides kept it afloat. The curvature of the convex

glass port served to nullify the refraction of the water, which, would

otherwise magnify underwater objects (Seaview included) about one-third,

thus making it necessary to work in a much larger underwater set to

achieve the same pictorial depth. |

|

|

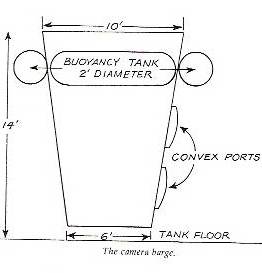

L.B.

Abbott drawing of camera barge above,

from his book on Special Effects. |

|

The curved

glass, cut down refraction and allowed normal

perspec-tive. An added advantage of

shooting through the curved glass using a 75m lens was that it

was possible to achieve a depth

of field ranging from 4 and 1/2 to 12 feet. In miniature

work, the depth of field factor is especially critical, particularly

when filming with CinemaScope lenses,

which characteristically lacked depth. |

Photographer

Winton Hoch & Irwin Allen

gaze up from within the camera barge. |

End Part 1. Part 2 coming soon.

| "Voyage

to the Bottom of the Sea" ® is a registered trademark

of Irwin Allen Properties, LLC. © Irwin Allen Properties,

LLC and Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. All rights

reserved. |

|